From the Chicago Reader, February 4, 1994:

ON THE BRINK OF ABSTRACTION:

JULIA

FISH

at Feigen,

through February 19

By Fred Camper

There is an aggressive, even imperial aspect to mainstream Western art.

From the monumental equestrian statue that etches its man-atop-horse form

into the sky to Jackson Pollock's huge drip canvases, large enough to seem

alternative landscapes, artists have placed an assertion of the human personality

— their subject's or their own — at the center of their works.

In our century a different tendency has emerged, most often in the work

of women artists. In the abstract paintings of

Agnes Martin,

Helen Frankenthaler, and

Mark Tobey, in the gentle interiors and star paintings of

Vija Celmins,

and in the observational street photographs of Helen Levitt, one finds

artists less interested in asserting their identity and not interested

in remaking the world. The viewer is asked to focus less on grand themes

— a victory in battle or the outline of a subject's soul — than on tiny

and apparently insignificant details. The artist who concentrates on minor

variations in pale colors placed between ruler-straight lines or on the

momentary poses of street kids offers no explanation for the order of things,

no heroic imagery. But this apparently narrower focus can offer a complete

vision, one asserting that it is not given to humans to rule or even understand

the whole word — that we can realize our best selves through a double journey,

one that marries external observation with inner vision.

I was not surprised to learn that Julia Fish cares very much about the

work of Martin, Tobey, and Celmins, among other  painters.

Her recent paintings and drawings, seven of which are currently on view

at Feigen — together with five 1991 works in a downstairs office — have

simple subjects. But the longer I looked, the more my experience of them

deepened. I was led less to identifiable themes, a definitive "vision of

the world," than to a deepening of my own inner awareness.

painters.

Her recent paintings and drawings, seven of which are currently on view

at Feigen — together with five 1991 works in a downstairs office — have

simple subjects. But the longer I looked, the more my experience of them

deepened. I was led less to identifiable themes, a definitive "vision of

the world," than to a deepening of my own inner awareness.

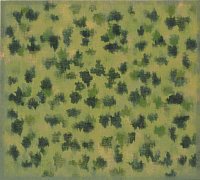

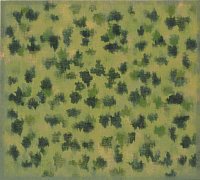

Fish's paintings have simple titles that do no more than modestly name

the subject that inspired them. Ivy is a green rectangle inside

a slightly darker border, within which float leaflike shapes. Fuzzy at

their borders and lacking precise details, these are hardly anatomically

correct leaves. Many are partly covered by gray-green blotches that could

be mistaken for areas where the paint has been partly scraped away, dulling

the color. Much of the work's power stems from such ambiguities. The leaves

hover against a green background, sometimes seemingly in front of it, sometimes

sinking into the dense green.

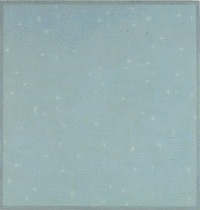

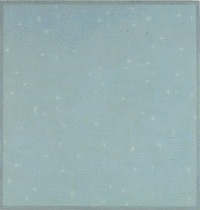

Flurries is my favorite work of the twelve. White flakes are

set against pale blue, again surrounded by a thin framelike band.  Though

the title suggests falling snow, there is no illusion of movement; the

viewer is suspended in time.

Though

the title suggests falling snow, there is no illusion of movement; the

viewer is suspended in time.

The apparent simplicity is deceptive. The blue background is actually

complexly textured, with patches of green and lighter blue; behind it lie

hints of tan, green, and yellow. Fish paints very slowly, building her

surfaces out of translucent layers of oil paint. Thus the perceived depth

effects in her work are not created by the "tricks" of Renaissance perspective

but by piling up layers of paint — a technique that, in different forms,

is as old as van Eyck. But if layering in van Eyck creates hyperreal colors,

Fish's colors are more tenuous, ethereal, changeable.

The subject-background relationship in Flurries is similarly

ambiguous. The white forms are not discrete; while their edges don't exactly

bleed into the blue, they aren't utterly separated from it either. The

pale blue itself seems suffused with white. As a result, it seems wrong

to call the flakes the "subject" and the blue the "background" — they are

equal partners in an amazingly gentle balance.

In many Renaissance portraits, perspective is used to articulate a relationship

of dominance: the wealthy merchant is shown against a window-view of his

city, which seems subservient to his controlling gaze. Fish has (as have

many of her colleagues) rewritten the power relations inherent in the traditional

painting of figure and ground. Snow and sky are equal but not merged; the

viewer can see one and then the other as foreground, and then see them

both on the same plane. After several minutes of viewing, the picture presents

all three possibilities at once. It is quiet yet alive, still but not static.

I felt the "still active equilibrium" Fish says she seeks.

Several of the paintings can be read in alternate ways — Flurries

as stars, Tide as a hilly landscape framing a mottled, multicolored

sky. The interplay between definite if indistinct forms and Fish's variegated

surfaces captures what Fish calls her "negotiation" between abstraction

and representation. The viewer stands as if on a threshold, looking inward

and outward at once: the external world constantly hovers on the brink

of abstraction, yet never disconnects from its roots in nature.

Fish, 43, grew up in a tiny town on the Oregon coast. Her parents encouraged

reading, drawing, and music and chose not to have a television. She remembers

"the tall forests and the Pacific horizon line" as formative presences.

Additional painting influences have included Romanesque mural painting,

Mondrian, and Monet. On first arriving in Chicago in 1985, she made paintings

based on her memories of Oregon landscapes. More recently, Fish, who is

a professor of art at the

University of Illinois at Chicago, has taken

inspiration from local sights.

Walk appears to depict rectangular paving stones or perhaps an

indoor tiled floor. Dark brown lines divide the tall rectangle of the canvas

into smaller, lighter brown boxes. No box is perfectly rectangular, no

line perfectly straight. The lines meet at slightly skewed angles; they

sometimes widen slightly around such intersections. The central contrast

is between geometric order and organic irregularity. Though the picture

seems dominated by its geometric configuration at first, it is the tiny

deviations that become most striking. What becomes strangely moving in

this work is the subtle difference between an 89-degree angle and a 91-degree

angle — a far cry from the grand gestures of Renaissance battle paintings

or of some modern abstract canvases.

This is not a narrowing of focus but rather a redefinition of what it

means to be human. Our attention should be directed not toward remaking

the world in our image but toward discovering the possibilities for spiritual

redemption in observations of the simplest of things. I was reminded of

William Blake's line "

To see a World in a Grain of Sand."

Each of her four Garden drawings on view are black-and-white

clusters of diverse biomorphic forms. While Garden #1 has empty

space between the shapes, the others are more densely packed; in Garden

#23, shapes are superimposed on each other and virtually no white paper

is visible. These improvisations on plant shapes are highly suggestive

— a garden of the imagination. These drawings are made on paper printed

with a grid apparently intended for Japanese calligraphy practice. While

the regularity of the grid makes an interesting contrast with the garden

shapes, I also thought of the long connection between calligraphy and landscape

painting in Japanese and Chinese art. Learning calligraphy was thought

to be the beginning of all artistic training, even more than figure drawing

was for Western artists; a close examination of older Japanese paintings

shows how much the brush strokes owe to calligraphy. The implication is

that Fish's shapes might form a new vocabulary.

Downstairs are four untitled "water drawings." Similar in most respects

to the Garden works, they are on unlined handmade paper, and the

shapes are much simpler — short, wormlike oblongs. As in Walk, I

sensed momentous implications in tiny variations between shapes. Yet while

focusing on tiny variations, I felt my mind starting to clear of all the

usual preoccupations — money, friends, sex, the future, the budget deficit,

the death penalty. To quote Fish, everything became "very still," and I

was transported to a rare, silent place. Later, I recalled having seen

four amazing "Seasons" landscapes by the great 15th-century Japanese landscape

painter and Zen monk Sesshu. While they depict the visible world with great

skill, the longer I looked at them, the more that world seemed to melt

away — as if the differences between rocks and trees, or between one season

and another, were mere transitory phenomena hiding deeper truths. Any skillful

painter can depict the visible; it is a rare one who can take us beyond

the visible.

© Copyright Fred Camper 1994

Links in this article:

Vija Celmins

Chicago Reader

Feigen

Julia Fish

Helen Frankenthaler

Agnes Martin

Monet

Sesshu

Mark Tobey

To see a World in a Grain of Sand

University of Illinois at Chicago

Home Film

Art

Other: (Travel, Rants, Obits)

Links About

Contact

painters.

Her recent paintings and drawings, seven of which are currently on view

at Feigen — together with five 1991 works in a downstairs office — have

simple subjects. But the longer I looked, the more my experience of them

deepened. I was led less to identifiable themes, a definitive "vision of

the world," than to a deepening of my own inner awareness.

painters.

Her recent paintings and drawings, seven of which are currently on view

at Feigen — together with five 1991 works in a downstairs office — have

simple subjects. But the longer I looked, the more my experience of them

deepened. I was led less to identifiable themes, a definitive "vision of

the world," than to a deepening of my own inner awareness.