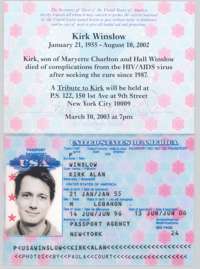

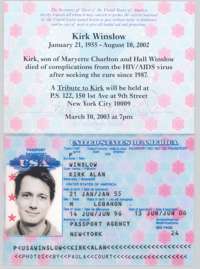

Remembrances of Kirk, by his Friends

This page includes a reminiscence of Kirk Winslow, by myself, Fred Camper, his friend of some 29 years, as well as remembrances by other of his friends who wish to contribute. If you would like to write about Kirk and have it posted here, or if you are posting something about him somewhere else on the Web and have a link I can include, please email me. One friend, David Moore, has contributed a reminscence, which is below mine.

In the fall of 1973, I was a teaching assistant in a course called "Contemporary Cinema" in New York University's Department of Cinema Studies, taught by Ted Perry. A few weeks into the semester, I was using a 16-millimeter projector to show a film excerpt to the small discussion section I was leading, and the bulb blew and needed to be replaced. I complained that it was too hot to grasp, and Kirk removed a triangular scarf he was wearing around his neck and handed it to me. I remember saying something to the effect that this wasn't really necessary, that I could find another way to get the bulb out, and he replied with a somewhat disparaging quip about the unimportance of his scarf, accompanied by something that piqued my curiosity about him much more — a smile that was a curiously original mix of boyish sweetness and amused self-deprecation. Years later, when I reminded him of this event, the moment I first noticed him, he replied with a comment about the scarf as a then-current but forever silly "gay boy" fashion.

What was it that was so extraordinary about Kirk? His way of experiencing art was not unrelated to something that the poet John Keats once referred to as "negative capability": Kirk gave himself over to numerous works of art, responding to all their nuances with an amazing degree of sensitivity, opening himself up to their aesthetic power and beauty rather than to considering them as works of the intellect — to the point where he seemed to almost vanish in the aesthetic experience.

I am reminded of Kirk's attitude toward film, and the extent to which it was related to my own, by an incident in the 1980s when he complained to me, with a mix of self-important annoyance and mordant humor: "You've ruined my social life! No one wants to go to the movies with me." He went on to explain that while others were happy to talk about whether they enjoyed the story, or the acting, he would usually be grousing about incompetent framing, badly timed camera movements, and incoherent editing. I have often retold that story as a half-humorous warning about the hazards of my approach. Attending to such things is what allows one to see the very greatest of films in all their complexity, but it also makes it harder to appreciate many films that others enjoy. Once I griped to Kirk about seeing three bad gay-themed shorts as part of my reviewing duties, and described one in which a key dramatic moment hinges on the pursuit of some Barbara Streisand records. Kirk's response was to condemn those films and other gay-themed things he disliked with an outraged, "For this we were queer?" Aesthetics mattered more to him than gender preference or tribal solidarity.

Paradoxically, Kirk was the first to admit that he was also a narcissist. He could even on occasion become bitchy, though I saw this happen only rarely. In one such incident, he stalked away from a planned meeting after I griped about his being forty minutes late. When he phoned later that day to apologize, I joked that he was a "drama queen," and he replied, "I’m not nearly well organized enough to be a drama queen," and he was right. He seemed a bit like a little boy lost in a world he didn't quite understand, endearingly ingenuous and sincere rather than manipulative. In his later years he had trouble even getting his belongings organized, and there was a period when he was homeless, living with friends. After he was diagnosed HIV-positive in 1989, he quit his job in great distress, working only part time, and sometimes not at all, in subsequent years. One sadness I have about Kirk is that I know that he could have achieved even more than he had in life, had not the news of his infection so effectively frozen him in place.

There was a day in 1986 when Kirk believed he had just become infected with HIV. I still remember his voice as he phoned me in near-terror: he had had unprotected sex with three different men — and it really though regretfully must be said that this was after it was known that condoms could be a barrier to the virus — and mentioned that one of the men in particular was someone he knew was a special risk. Now he felt a bit sick and his lymph nodes were enlarged. Later I read that such symptoms were often a sign of first infection, though Kirk much later expressed doubts that that was the moment for sure. But it does seem almost certain that if that wasn't the moment of his infection, it would have been earlier rather than later, which means he was a long-term survivor. Kirk managed his own care, wisely avoiding AZT when it was first advocated. The newer drugs helped for a while, but because of side effects he didn't take them consistently. Near the end, he was diagnosed with lymphoma, and the last time I spoke with him, by telephone from his hospital bed on August 4th, 2002, he expressed doubt about his survival. His doctors had told him that his weakened body could not withstand treatment for lymphoma, and he agreed with them, so there seemed to be no way to combat it. Still, I had no idea that he would be dead in six days.

Kirk had in some ways never fully formed what most of us would regard as an "adult" personality, with all those particular quirks of taste and vision that can, by becoming a guiding purpose, both propel one forward through life. Yet such a purpose can be limiting, a distorting screen through which all inputs must pass, a filter that colors the external world to the point of cutting one off from it. Kirk, by contrast, retained some of the openness of childhood or early adolescence, and in this regard he was one of the best appreciators I have ever known of a wide variety of arts, whether film, classical music, dance, literature, theater, opera, painting, sculpture, or architecture.

He also cared about people, and despite his self-centeredness enjoyed contact with a wide variety of folks, especially those involved with the arts, and tried to help others whenever he could.

For most of the time I knew Kirk, decades after the semester when I'd had him as a student, he would introduce me as his "teacher." At first this made me a bit uncomfortable, as we had become friends, but eventually I realized that yes, he had been very much influenced by my own aesthetic, and that I should accept the degree to which I was being honored, and even perhaps be a bit proud of it, especially as it was coming from someone who was himself so exacting in his standards.

At some point in the late 1980s, I told Kirk, knowing he was both an opera lover and an admirer of the films of Warren Sonbert, about attending several operas with Warren in Chicago — Warren seemed to have an almost endless supply of free tickets, perhaps because he wrote about opera for The Advocate under the pseudonym "Scottie Ferguson" (a reference to Alfred Hitchcock's Vertigo). Kirk replied, "Oh, Warren Sonbert, oh, he's a real opera queen." I made a hand-written faux gossip column with names in boldface that included that quote along with a couple of other tidbits, ascribing the "opera queen" comment to "a gay boy we know," which constituted part of a letter I sent to Warren. Warren was amused, and replied to the effect that "when you next see your gay boy friend, in a uncompromising situation I'm sure, tell him that while I don't mind the appellation, I don't dress up as opera characters, etc." I also made a point of telling Kirk about what I'd written Warren, and that of course I hadn't named him. But it says something positive about both of them that Kirk then introduced himself to Warren at one of Warren's New York screenings as the person who'd called him an "opera queen" — and they become good friends. Warren wrote me that Kirk was "very sweet," and he added Kirk to the long list of people he tried to always call on visits to New York.

After Warren died from HIV in 1995, I expressed regret to Kirk that I hadn't seen more of Warren in his last years, and Kirk suggested that one way I could respond would be by seeing more of him — which I did, and was glad to do. Still, it always annoyed me a bit that I could see Kirk only on visits to New York City; he never once visited me in Chicago, where I have lived since 1976. But there's a pattern there that goes way beyond Kirk: almost every significant friend I've made over the years, whether from Toronto or New Mexico or Switzerland, has visited me at least once in Chicago, as I generally have them, except for the New Yorkers, virtually none of whom have ever visited me. This doubtless has something to do with the attitude of New Yorkers toward the rest of the world! Still, Kirk's point was well taken: regrets over the dead should remind us of our interest in the living.

A fact that is true for almost all of us was present to a heightened degree in Kirk: his strengths were also inevitably his weaknesses. Being able to almost "become" experiences outside of himself perhaps was a consequence of his having a relatively weak sense of his own identity. Though he was narcissistic, he didn't try to impose any particular version of the self onto others, or onto the world. He didn't convert his experiences of particular works of art into advocacies for agendas of his own, as so many of us do, often without realizing it. And because he cared so much, he was frequently enraged. Some of his rages could seem excessive, as when he complained with increasing intensity in each passing year that the world was becoming a living hell. It seemed to me that he was projecting his own lifelong depression, and the way it led him to despair, onto the external world. But then, just after September 11, 2001, Kirk seemed almost relieved, sporting a subtle "I told you so" air, as if his sense of increasing horror had been proven correct. In spite of the almost unimaginable awfulness of the precipitating event, one had to chuckle a bit.

Other times, even while urging Kirk to try not to let his anger affect him so personally, I shared his rages: against projection of films so incompetent as to amount to butchery, against poorly-made "restorations" of older films, against architecture so horrible as to be almost obscene (we both shared a hatred for the shopping mallish atrium that seems so out of place in the Morgan Library), against the actions of people who seemed to be making the world worse through ignorance, bad taste, or lack of care. Kirk's great strength, but one that also made him unhappy, was that he cared too much.

Kirk's rages stemmed at least in part from his loves. Because he so loved the highest possibilities of human culture, he couldn't stand those things that might deface or destroy them. He sought an aesthetic perfection in the world and in his own life that was, in my view, fundamentally unattainable, but in that quest he also celebrated some of the things I most care about, while underlining all those forces that drag down human achievement, that degrade that which is best in us.

I last saw Kirk was on June 28, 2002. A friend of mine named Jack, with whom Kirk had also become friends, had long wanted me to meet a friend of his named Fred, a fellow film-lover. Jack had been proposing that the three of us have dinner on one of my New York visits. Knowing that Kirk also knew and liked Fred, I suggested including Kirk in the dinner, and all were pleased with the idea, though when I also asked Kirk to choose the restaurant, his first response, enunciated in a breathless huff — "There are no good restaurants left in New York" — seemed too-humorously stereotypical of his later years. But soon he settled on the vegetarian Zen Palate, on Broadway at 76th Street, which turned out to be excellent, and Kirk was in fine form that evening. We had spirited discussions on a variety of topics, with Kirk taking notes on the paper tablecloth, and when I started to spew out a list of my favorite painters impromptu, Kirk asked me to slow down so he could write them all down, which he did, pulling the tablecloth off the table with a flourish when he departed and bringing it home for his "archive." After he died, I was so glad I could remember what a fine time we all had at that dinner, and how much Kirk seemed to enjoy it, rather than regret that I hadn't managed to see him on my visit. I've made this page to help myself and others remember him, but, following his advice, I'm also taking care not to let other friendships languish, trying to be true to the great challenge of living in the present.

But of course memories can be part of each of our present lives. Kirk's close friend Ken Goodman vanished in 1995, Kirk had soon suspected it was a suicide since, very ill with the last stages of HIV/AIDS, Ken had talked about drowning himself in the Hudson. After he disappeared, Kirk and Ken's other friends and family members carefully went through Ken's possessions and distributed each to the person they thought would most appreciate it. I got two books, and in an art review I wrote about the AIDS-haunted works of Robert Blanchon not long after, I found myself telling the story of that gift, and reflecting on the extent to which it conjured up my memory of the one time I had met Ken. I'm pleased that I still have some of the packets that Kirk sent me. A typical one might include a magazine article, an art review, a concert program, and an art exhibition card — assembled with the aesthete's great care that Kirk brought to every aspect of his life.

What most matters to me now is the extent to which each person we meet helps shape the person we become, and how we each live on in each other. I may have helped shape Kirk, but he also helped shape me.

David Moore, Jr., of Minneapolis, remembers:

In 1971-72 I was a fairly guileless tenth grader starting at the Putney School in Vermont, and Kirk Winslow was, as I recall, a senior. He and I worked together in the afternoons on the school’s stage-crew, where I learned the rudiments of scene carpentry, painting and lighting. I remember Kirk seemed already incredibly knowledgeable in all these skills, lightning quick, resourceful -- and, yes, he indeed would punctuate fierce perfectionistic effort with inordinate flair. Diamond brilliance. A sulk-as-consummate-showman. Each afternoon would being with our riding an old flatbed truck down the road to the school’s barn-theater. The rest of us would sit, but Kirk often would stand, and as the truck turned in reverse and backed slowly up to the barn’s entrance he sometimes would leap off its back end, landing more-or-less effortlessly to stride inside and be the first to seize tools and work. It was like a movie stunt, loud clopping boots and all.

Kirk’s French seemed fluent, his literacy light years beyond anything I might ever grasp, his views of life wiser than any I’d ever encountered.