Friedrich has remarked that it was only when she began writing about

herself in the third person that it became possible to tell her stories

at all. Perhaps the intensity of the material required that degree of distance;

at any rate, the "she" suggests that we are watching the story of a person

not yet fully formed, not yet ready to assert herself as an "I" in the

world. The awkwardness of the narrator's voice — a young girl reading often

complex texts — is an appropriate additional kind of displacement. However,

the girl's voice varies so frequently in its degree of emotional inflection

that its effect is a little jarring.

The film's variety of connections results in a collage of extraordinary

richness, a portrait of a persona that is somewhat less than unified. As

the adult woman struggles to emerge from the skein of family influences,

she begins to take actions to assert her own autonomy. On a narrative level,

this process climaxes when she decides not to swim across a lake

that her father had often swum (he had also tried to scare her from swimming

in it when she was a child). But on a cinematic level,

the climax comes

earlier, in a powerful section titled "Kinship." From the point of view

of a traveler, presumably Friedrich, we look through the window of a plane

as it takes off. Then there are images of Death Valley, as our protagonist

walks about accompanied by a friend. Intercut periodically are images of

nude women in a shower and sauna; at one point two women embrace. The little

girl whose father had both introduced her to and made her scared of the

world now has a physicality — an ability to move through space — and a

sexuality of her own.

the climax comes

earlier, in a powerful section titled "Kinship." From the point of view

of a traveler, presumably Friedrich, we look through the window of a plane

as it takes off. Then there are images of Death Valley, as our protagonist

walks about accompanied by a friend. Intercut periodically are images of

nude women in a shower and sauna; at one point two women embrace. The little

girl whose father had both introduced her to and made her scared of the

world now has a physicality — an ability to move through space — and a

sexuality of her own.

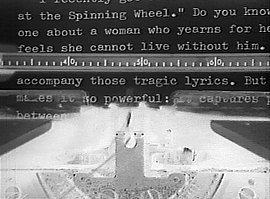

But since one of Friedrich's themes is the continual interdependence

of past and present, her film cannot end here. In fact, the sequence just

described is accompanied by a discordant and unexplained  element — a German

art song on the sound track. A few sections later, in "Ghosts," a typewriter

is seen in negative typing out a letter from Friedrich to her father. On

the sound track, instead of the young narrator's voice, we hear the typewriter

keys, giving the section a harshness, even a confrontational directness,

that most of the other sections lack. In the letter, she describes her

mother's loneliness after her father left the family. Mother would rush

the children to bed each evening, and then listen, alone, to an album of

Schubert lieder. Her favorite song was also young Su's favorite, "Gretchen

at the Spinning Wheel" — the song we heard earlier. Friedrich explains

in her letter that she only recently learned the translation of the lyrics,

which describe a woman who years for her absent lover and feels she can't

live without him.

element — a German

art song on the sound track. A few sections later, in "Ghosts," a typewriter

is seen in negative typing out a letter from Friedrich to her father. On

the sound track, instead of the young narrator's voice, we hear the typewriter

keys, giving the section a harshness, even a confrontational directness,

that most of the other sections lack. In the letter, she describes her

mother's loneliness after her father left the family. Mother would rush

the children to bed each evening, and then listen, alone, to an album of

Schubert lieder. Her favorite song was also young Su's favorite, "Gretchen

at the Spinning Wheel" — the song we heard earlier. Friedrich explains

in her letter that she only recently learned the translation of the lyrics,

which describe a woman who years for her absent lover and feels she can't

live without him.

Now — and particularly on a second viewing — we are able to understand

"Kinship" in a new way. The adult Friedrich has defined herself in part

in opposition to the song, as represented by her postdivorce mother: not

at home alone, but seeing the world; not heterosexual, but lesbian. And

yet, as is so often true of Friedrich's connections, the two elements (song

and image) that relate as opposites also relate as identities, for the

sexual footage is intercut with the travel footage, representing a different

time and place: our adult traveler is at the moment, or so it would appear,

also without a lover.

More complete explanations of things seen earlier are offered more than

once in the film. This pattern is a beautiful way of expressing the dependence

of the present on the past: however much one may think one is living in

the present, however ordinary one's present moment may seem, the past will

always return to assert its grip. Nonetheless, the adult Friedrich continues

to struggle to emerge. We see her as an adult for the first time when the

narrator describes the adult Friedrich (now "the woman") observing her

father treat his young daughter, her stepsister, in the same kind of sternly

inconsiderate way that she remembers so well from her own childhood. As

the narrator describes how the woman watched this scene with horror, while

sipping lemonade, we see the adult Friedrich, alone in her bathtub, perhaps

a bit depressed, drinking beer from a bottle. But witnessing the father-daughter

scene as an adult may have been also liberating: the sequence ends with

the adult Friedrich typing out the story on her typewriter, now seen in

positive rather than the negative of the earlier typewriter sequence. She

has thus finally emerged, from all the displacements of black-and-white

negative, third-person narration, and home movies, as the film's independent

center.

sipping lemonade, we see the adult Friedrich, alone in her bathtub, perhaps

a bit depressed, drinking beer from a bottle. But witnessing the father-daughter

scene as an adult may have been also liberating: the sequence ends with

the adult Friedrich typing out the story on her typewriter, now seen in

positive rather than the negative of the earlier typewriter sequence. She

has thus finally emerged, from all the displacements of black-and-white

negative, third-person narration, and home movies, as the film's independent

center.

Such moments of clarity and independence do not obviate the continual

return of Friedrich's principal persona — a being hopelessly divided, irreparably

torn between present and past, between fantasy and reality, between a remembered

family past and an adult present, forged outside of the family unit. But

such divisions and contradictions should not be seen in a wholly negative

light. What Friedrich cannot be — a person who regards her consciousness

as unified and integrated, and who organizes the world around that consciousness

— is mirrored in what the film's style generally avoids. Its gritty, nonglossy

black and white mimics the look of the home movies that are so prominent

in its imagery. Unlike the static, formal compositions in more conventional

movies, Friedrich's hand-held camera responds to her bodily movements and

attitudes of the moment.

In the films of Stan Brakhage, a similar use of small movements filmed

by a hand-held camera produces a musical rhythm that ultimately imposes

the sense that a single personality, even a single body, is organizing

the world. In contrast to Brakhage's vision of the transcendent self, Friedrich

as well as other younger filmmakers have posited a self that is contingent,

malleable, internally divided, and very much a product of its environment.

In the work of an earlier generation of personal filmmakers the "self"

is taken as a given, springing full-grown like Athena from Zeus's brow;

Friedrich's self is constantly in the process of being formed and reformed,

from the moment the sperm enters the egg, through all her experiences with

her parents, through all the choices she makes — and Sink or Swim

lays that process of formation bare, surrounding the protagonist with the

images and sounds that influence it.

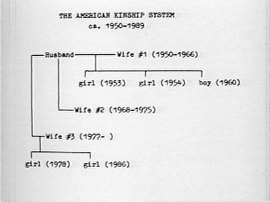

A humorous moment late in the film speaks directly to Friedrich's conception. The narrator says that after the father left the family, they were able to buy a television, something he had always forbidden, and we see images from Father Knows Best.

In one shot, we see the faces of three scrubbed and smiling kids, all in

a line, object-like as only American mass culture can make them. Friedrich

is making fun of this concept of the happy nuclear family, and the artificial

media image gives Friedrich's personal stories a social dimension as well.

But there is another, deeper joke at work. The compositional perfection

of this image, and the way the children's faces are reduced to objects,

is utterly contrary to the style of Friedrich's film. It contradicts the

style of the home movies she uses, with their jerky images of active children,

but it contradicts the overall space of the film as well.

A humorous moment late in the film speaks directly to Friedrich's conception. The narrator says that after the father left the family, they were able to buy a television, something he had always forbidden, and we see images from Father Knows Best.

In one shot, we see the faces of three scrubbed and smiling kids, all in

a line, object-like as only American mass culture can make them. Friedrich

is making fun of this concept of the happy nuclear family, and the artificial

media image gives Friedrich's personal stories a social dimension as well.

But there is another, deeper joke at work. The compositional perfection

of this image, and the way the children's faces are reduced to objects,

is utterly contrary to the style of Friedrich's film. It contradicts the

style of the home movies she uses, with their jerky images of active children,

but it contradicts the overall space of the film as well.

In a section titled "Quicksand" the narrator recounts a story about

Friedrich's father forcing her to watch a scary movie. The imagery connects

allusively, rather than directly, to the title and to the story told on

the sound track. We see footage taken from a roller coaster in relatively

short takes and edited with a jagged, unpredictable rhythm; shots rarely

feel as if they are brought to completion. This style combines with the

sweeping movements of the roller coaster to create the feeling of a space

that is continually dividing and breaking apart in ways that cannot be

anticipated — one sees a vision of the world fraught with peril, unexpected

voids, quicksand.

In a section titled "Quicksand" the narrator recounts a story about

Friedrich's father forcing her to watch a scary movie. The imagery connects

allusively, rather than directly, to the title and to the story told on

the sound track. We see footage taken from a roller coaster in relatively

short takes and edited with a jagged, unpredictable rhythm; shots rarely

feel as if they are brought to completion. This style combines with the

sweeping movements of the roller coaster to create the feeling of a space

that is continually dividing and breaking apart in ways that cannot be

anticipated — one sees a vision of the world fraught with peril, unexpected

voids, quicksand.

This vision, of space and of the self, lies at the heart of Sink

or Swim. The surprising and playful stylistic shifts, between home

movies, newly photographed footage, and rephotographed older footage (the

nude women in "Kinship" are from Friedrich's first film); the disparities

and displacements between image and text; the disruption when the text

directly names what is seen in the image — all these suggest nothing less

than the flailings of a beginning swimmer trying to come to terms with

inner and outer chaos. The difference is that through her imaginative control

of her medium, Friedrich has raised those flailings to the level of art,

and in so doing has expressed both their regressive terror and their forward

progress.

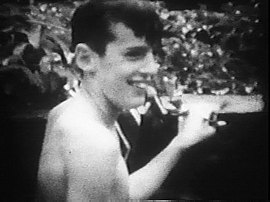

In the film's final image she manages not only to combine the diversity

of her themes in a single cinematic moment, but to go beyond them as well,

with an aching expression of haunting power. The film's reverse alphabet

has just concluded, and we see a shot of Friedrich as a girl, posing for

the camera in a manner rare in the film and vaguely reminiscent of the

shot of the three children from Father

Knows Best. She stands in a bathing suit with an oddly frilly skirt

as an adult voice — Friedrich's own, in fact — begins to sing the ABCs.

Shortly after she begins, the song begins again, her voice superimposed

over itself, in the manner of a round. At the same time the image is superimposed

over itself, paralleling the music, until suddenly all the aural and visual

superimpositions drop out. The child is then seen alone again, in freeze-frame,

while her single voice sings the last line of the song, "Tell me what you

think of me."

of her themes in a single cinematic moment, but to go beyond them as well,

with an aching expression of haunting power. The film's reverse alphabet

has just concluded, and we see a shot of Friedrich as a girl, posing for

the camera in a manner rare in the film and vaguely reminiscent of the

shot of the three children from Father

Knows Best. She stands in a bathing suit with an oddly frilly skirt

as an adult voice — Friedrich's own, in fact — begins to sing the ABCs.

Shortly after she begins, the song begins again, her voice superimposed

over itself, in the manner of a round. At the same time the image is superimposed

over itself, paralleling the music, until suddenly all the aural and visual

superimpositions drop out. The child is then seen alone again, in freeze-frame,

while her single voice sings the last line of the song, "Tell me what you

think of me."

Just as the film itself crosses several genres and contains a variety

of styles, so the film as a whole can be taken in several ways. It is not

only a film about the artist's father, not only an autobiography, but,

as this ending makes clear, it is also a letter to her father, a larger

version of the letter we see her type in the film, which she ends by typing

"P.S. I wish I could mail you this letter." The film, too, is a letter

she cannot send, a letter filled with reproach, criticism, anger, but also

gratitude, even love. The film in fact offers evidence to her father that

in some ways he taught her well: not only does she know her alphabet, but

she knows it backward. But more, the film's incessant story telling is

evidence that the book of Greek myths he gave her as a child and his encouraging

(sometimes undercut by discouraging) her to tell him stories have had their

effect. On one level, the film is a gift to her father, a gift that, in

a contradiction that perhaps mirrors many of the film's smaller contradictions,

she cannot proffer.

Of course, "Tell me what you think of me" is also addressed to the audience

— the filmmaker asking for approval. But perhaps the strongest meanings

to the last line are to be found if one considers it addressed directly

to her father. After all the film's progression, after all the difficulties

that the protagonist endures in order for her adult identity to emerge,

there is something chilling in the way the film reverts to this child's

request for approval at its end. The film and its adult maker know this

terror well, as can be seen by still another aspect of the alphabetical

ordering of the film. The reverse order, in its arbitrariness and oddness,

can be seen as the creative assertion of an adult, taking the things she

has been taught and reordering them in her own way. That she chooses to

order the alphabet in reverse makes the reversion to the "correct" order

in the song all the more horrible: the autonomous adult has once again

reverted to the uncreative child, parroting rather than creating, seeking

approval rather than going off on her own. But in the regression, and in

the obvious contrast between reverse and forward orders, is also the adult's

cry of rage at the way the past keeps returning. She still seeks Daddy's

approval, but she is also enraged that she continues to feel this need.

The film's ending is a cry of protest that a child, an adult, anyone, should

feel such dependency: and so the final image lingers, in the memory, like

a scream that cannot be answered, like an open wound that cannot heal.

Copyright © Fred Camper 1991.

Su Friedrich's Sink or Swim is available for rental from

and

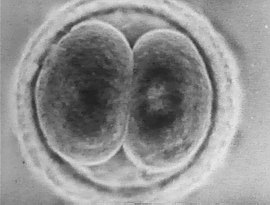

finally an embryo. As the zygote begins to divide, the voice of the young

girl begins to tell the story of Athena,

who, unique among Zeus's daughters, sprang full-grown from his brow. The

ironic disparity between the facts of human reproduction as seen in the

imagery and the myth of asexual reproduction heard on the sound track introduces

one of the film's central conflicts, the struggle of a child to create

her own self, in the face of the "facts" of the world that her parents

provide her. This myth and others and stories from Friedrich's own life

are told on the sound track in the third person by the narrator. We soon

find out that when she was very young Friedrich's father gave her

a book of Greek mythology and that she has at least since then been fascinated

by stories.

and

finally an embryo. As the zygote begins to divide, the voice of the young

girl begins to tell the story of Athena,

who, unique among Zeus's daughters, sprang full-grown from his brow. The

ironic disparity between the facts of human reproduction as seen in the

imagery and the myth of asexual reproduction heard on the sound track introduces

one of the film's central conflicts, the struggle of a child to create

her own self, in the face of the "facts" of the world that her parents

provide her. This myth and others and stories from Friedrich's own life

are told on the sound track in the third person by the narrator. We soon

find out that when she was very young Friedrich's father gave her

a book of Greek mythology and that she has at least since then been fascinated

by stories.